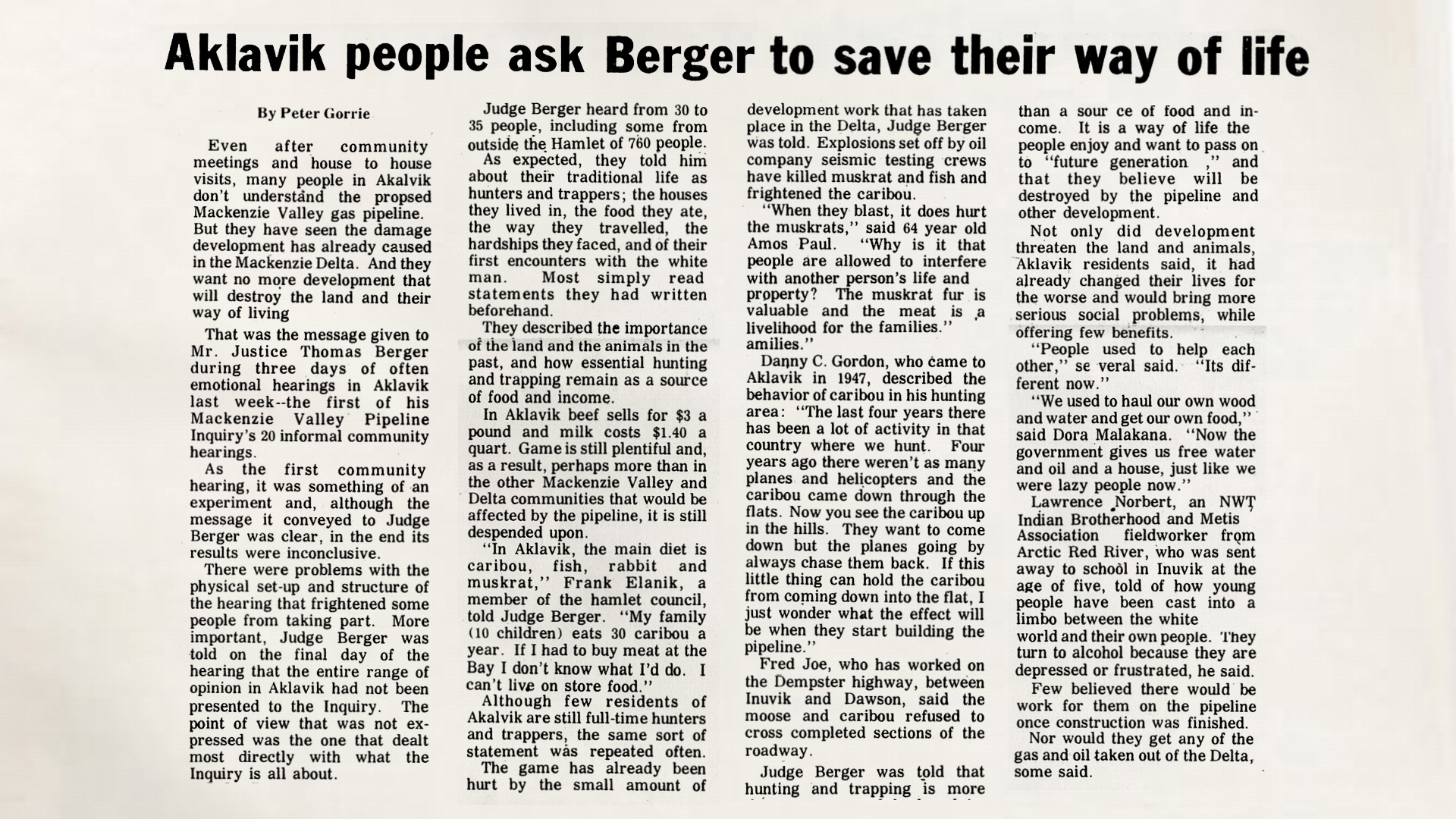

News of the North

Interview with Peter Gorrie by students at Echo Dene School, Fort Liard, NWT

Q. When did you decide to be a journalist?

Good question: How did I, born and raised in

Toronto, become a reporter at the Berger

Inquiry in Aklavik? Environmental issues were

always important to me. Near home I saw

factories, highways and suburbs sprawling

on some of the world's best farmland.

Journalism grew attractive. It promised to

put me in the middle of events. I began

working at student newspapers. It was

difficult at the start: I was shy and it took

a long time to summon the courage to

phone for an interview. But I persevered.

Q. How did you begin writing ?

I got a job at the Ottawa Citizen, first as

a copy boy, then, as a reporter. I loved

the process of building a story. It's like

assembling a puzzle - gathering facts

and quotes, figuring out how to arrange

them to tell a meaningful story and, then,

editing the words and grammar to make it

stronger.

The Citizen was an ideal place to start,

because it had space for long features.

They threw young reporters into difficult

assignments and had tough editors whose

critiques were better than journalism school.

Q. How did you prepare?

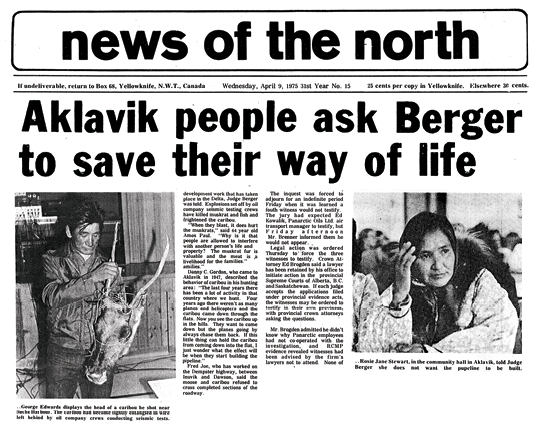

I'd been in the NWT for only three months

when we flew to the Delta for the first

community hearing, I had never been outside

of Yellowknife. It was April 2, still cold and

snowy: a world completely new to me.

I wandered around the hamlet, shooting

photos of the community. I talked briefly

with a few people who spoke English -

briefly, because both they and I were shy.

I went to a dance. By the time the hearing

began, I had learned something of Aklavik's

community life. I was ready.

Q. How did the Aklavik hearing change you?

Through it all I came to a conclusion that

has coloured my views ever since: Aklavik

was home to nearly 800 people, who had

every right to be there, and every right,

also, to object and resist when someone

else tried to transform or take that home

and way of life from them.

It was up to them to decide the speed of

change. Without that, they were facing

more of the colonialism that has persisted

throughout human history. Here was,

perhaps, one last place to keep it at bay.

Q. Did your views affect your story?

At the News of the North, the publisher

Colin Alexander and I had different opinions

about the Berger Inquiry. He wanted the

pipeline built. But I had grown up with the

1960s desire for change. I was supportive

of the Inquiry. I believed anyone who would

be impacted by the project should be heard.

Despite our differences, Colin published the

stories I wrote without changing them. In

return, I tried to present all sides, although

I gave more space to pipeline critics as well

as Dene and Inuit speakers.

Tip: Work from Memory

For me, the best way to write a story was

to start from memory, without looking at

my notes or listening to voice recordings. I

simply wrote down what came to my mind

first, because that was likely the most

important element for the story.

I wrote as much as I could from memory,

pretending I was telling the story to friends

or family. When I came to a place where I

wanted to use a quote or needed to check

a fact I'd mark the spot. Later, I'd find

what I needed in the notes or recordings.

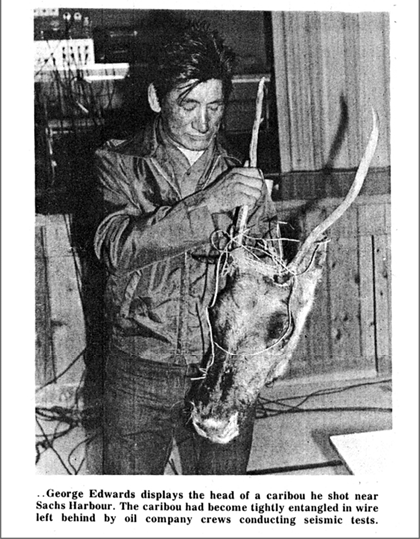

Tip: A Picture = 1,000 words

On my first assignment, I was to go to the

Giant Yellowknife mine to take photos of a

nurse clipping hair from miners, to test for

arsenic poisoning. This was in the days of

film cameras. I took photos from all angles.

Very pleased with myself, I raced back

to the office to brag. The sinking feeling

began when I started to rewind the film.

There was none of the usual tug as I

turned the wonder on top of the camera.

The feeling got worse when I kept winding

and realized there was no film in the

camera.