Patrick Scott

CBC Cameraman

Q. How did you get your job?

I was working at CBC Vancouver. One day a reporter came in with a job posting for a cameraman to do the CBC coverage of the Berger Inquiry. I loved the idea of living there. And I got the job!

At the Formal hearings of the Inquiry I had to shoot bits and pieces throughout the day because of the film costs, so most of the day I sat in the Inquiry hearings and listened, picking my story.

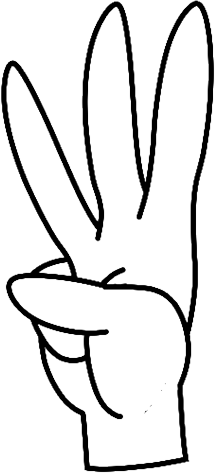

Photo: Michael Jackson

Q. Who was on the news team?

The first Community hearing was held in Aklavik. The CBC sent its team of Indigenous language reporters up to the Delta to cover the hearings: Joe Tobie, Louie Blondin, Abe Okpik, Jim Sittichinli and one non-Indigenous reporter, Whit Fraser.

We drove from Inuvik to Aklavik with our gear. It was a testing ground. How would the community hearings go?

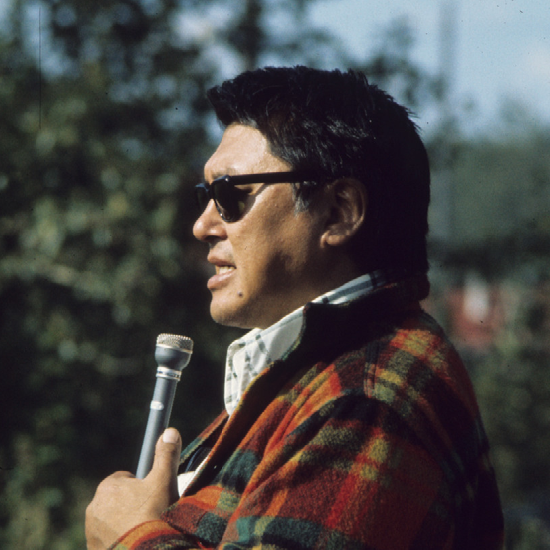

Photo: Pat Scott

Q. How did you find your stories?

The Judge started each hearing by saying: 'I'm here to listen.' People started telling stories of living on the land. The Judge sat and listened and listened. He stayed until everyone who wanted to speak had had a chance.

Every day, the reporters did a news report in their own language. They were skilled. They translated the testimony into language understood by people living in bush camps across the north. They were completely at home with the challenge.

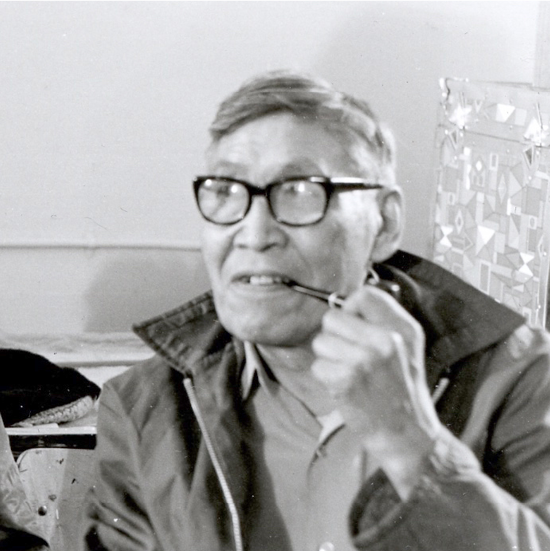

Photo: Government of Canada

Q. Why were these reporters special?

Each day I prepared a television report in a different language. It was go, go, go. We'd sit in the Inquiry all day and then churn out reports all evening. A dynamic time.

Aklavik was home turf for Abe Okpik. At the hearing he told of falling through the ice in the Delta, into an ice cave. The lake was frozen right to the bottom. The experts from the oil industry were amazed - they weren't aware of that.

Photo: Michael Jackson

Q. What special moments do you recall?

In Old Crow, Jim Sittichinli was translating for an expert who was giving evidence about caribou fences that had been carbon dated - they had been used by the Gwich'in 30,000 years ago.

Jimmy stopped translating and said: 'Oh, yeah, I remember hunting with caribou fences when I was young.' It was delightful to see the look of amazement on the face of the so-called 'expert'.

Photo: NWT Archives

Photo: Jerri Thrasher

Q. Did you give evidence at the Inquiry?

As I heard the stories, I was overwhelmed by the passion of what the land meant to people. So when the Inquiry went to Toronto, I decided to make a speech.

Industry and government were saying: 'We need the natural gas right now.' But in Toronto we were staying in a hotel that had heated floors. Why were we wasting energy in such a frivolous way? Forty-five years later, I'm still preaching the same message."

Photo: Linda MacCannell

Tip#1: Test your Equipment

Here's my first tip: Before you start shooting, test your equipment.

One time Whit and I were sent to Goa Haven to cover a story. I was carrying an instant-load camera. I was supposed to check it for grit that would scratch the film. But I forgot.

After Goa Haven, we were stuck for three days by bad weather. When we got back to Yellowknife, I sent the film for processing and - nothing.

Tip#2: Lousy Sound, Lousy Story

Before you start to shoot, listen to the noises around you. Is there any noise that could distract from the voice of the person you are interviewing? The noises may come from nature, or they could come from people whose conversation drifts into the range of your microphone.

Shoot a 30-second clip and play it back. If there is a distraction, move the interview to a quieter spot.

Tip#3: Don't Move the Camera!

Always use a tripod. Once you have a a set up that pleases you, set your frame. Then, don't move the camera. Don't zoom in or out, don't pan across the shot. If you move the camera, it will create problems when you try to match sequences when you edit.

When your interview is complete, take a series of shots that the editor can use as cutaways. Look for shots that complement the ideas discussed in the interviews. Then your final edit will flow.