Environmental Debate

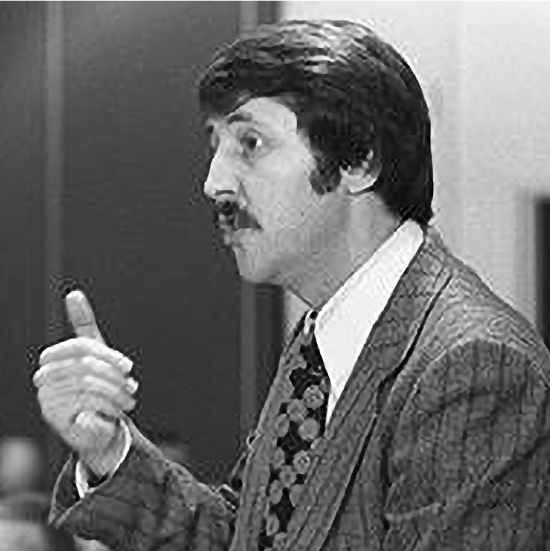

An interview with Russell Anthony, counsel for the Environmental Groups

Q. In the 1970s, was it unusual for

environmental groups to be represented at

inquiries?

Early in the 1970s, getting environmental

evidence into hearings was very difficult.

The hearings were between industry and

the government, and the public was not

invited to participate. Gradually, some of

the younger lawyers began trying to impose

ourselves into regulatory hearings.

Photo: NWT Archives

We got beaten up quite a bit. There was a

proposal in the Yukon to dam the Aishihik

River, which would destroy Aishihik Falls and

a historic aboriginal burial ground. I went

up there and slept on the floor of a local

resident's house.

We attended a hearing but were not

allowed to speak. Months later, they

relented. It was the first time that

happened.

Photo: Wikipidia

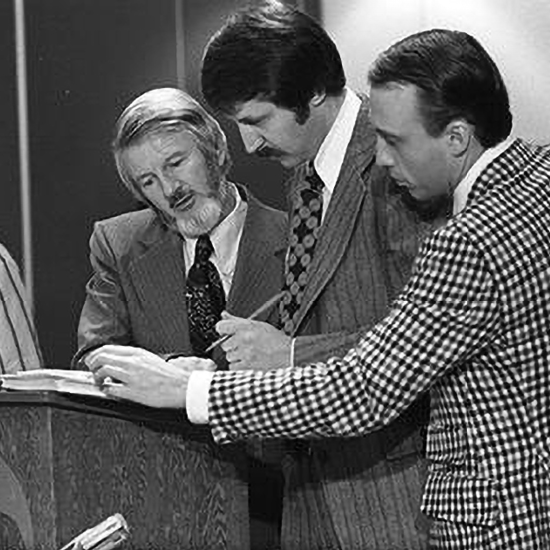

Q. How was the legal case for the

environmental organizations organized?

Judge Berger was the first to find funding

so environmental groups could be heard. But

there were so many interests that wanted

to be present: how do you accommodate

that?

Berger got the environmentalists from the

north and south together and said: 'I will

fund one environmental voice. So you're

going to have to form a coalition and

support it, all of you.'

Photo: NWT Archives

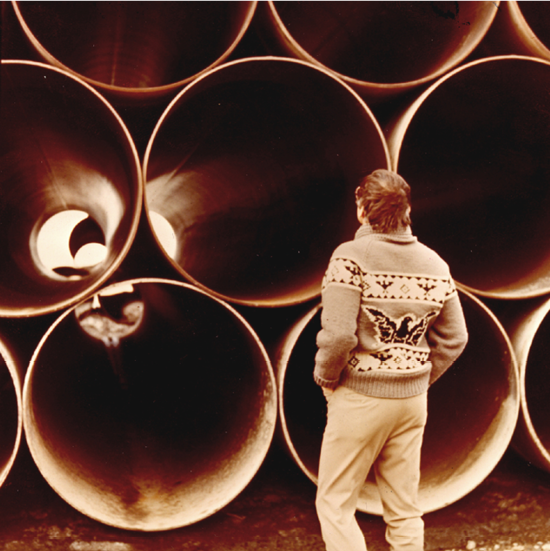

Q. What was the primary concern that

environmental groups had about the pipeline?

The Berger Inquiry was looking at a gas

pipeline. But we were concerned that later,

when an oil pipeline was suggested, the

companies would say: 'Let's not disrupt

another area. Let's put the oil pipeline next

to the gas pipeline. And then we might as well

put in a road.'

So we saw the pipeline as a transportation

corridor.

Photo: The Berger Inquiry

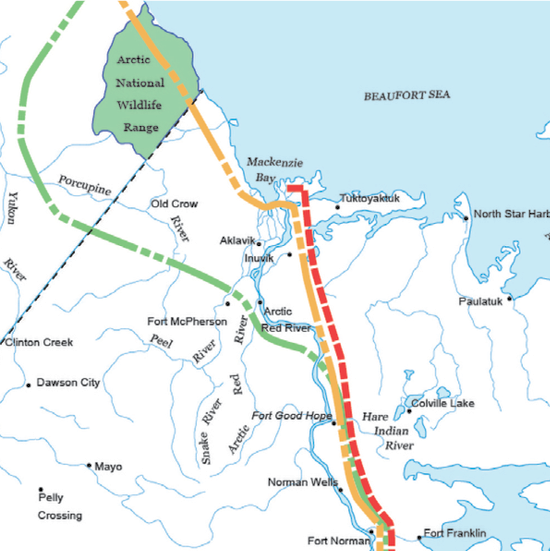

Q. What evidence was particularly

important?

The route proposed by Arctic Gas would

cross the North Slope of the Yukon

where the Porcupine caribou herd was an

international treasure. What does a pipeline

do to caribou migration routes? It would

cross a critical calving area.

So we argued that at certain times of the

year, even a minor disruption would have

catastrophic impacts.

Image: Markus Radtke

As the counsel for the environmental

organizations, I had to make sure our

evidence was credible. Sometimes I sat down

with a scientist and he said: 'This will never

happen.' I had to question him: 'Never? Or it

just hasn't happened yet?'

Secondly I had to look for inconsistencies.

So imagine a representative for the pipeline

companies said: 'Don't worry, we can repair

the pipeline within 24 hours.' Then we would

comb through the evidence to find where

another representative said: 'We are going

to decommission the roads.' We had to ask:

which of these things is true?

Photo: NWT Archives

Finally, we had to admit to ourselves: this

pipeline might go forward. If so, we had

to recommend the controls, systems and

procedures that should be in place to

protect the environment. Our team pulled out

all the important information so it didn't get

lost.

As a counsel, that was my job: to structure

the argument to have impact and credibility.

Photo: UWinnipeg