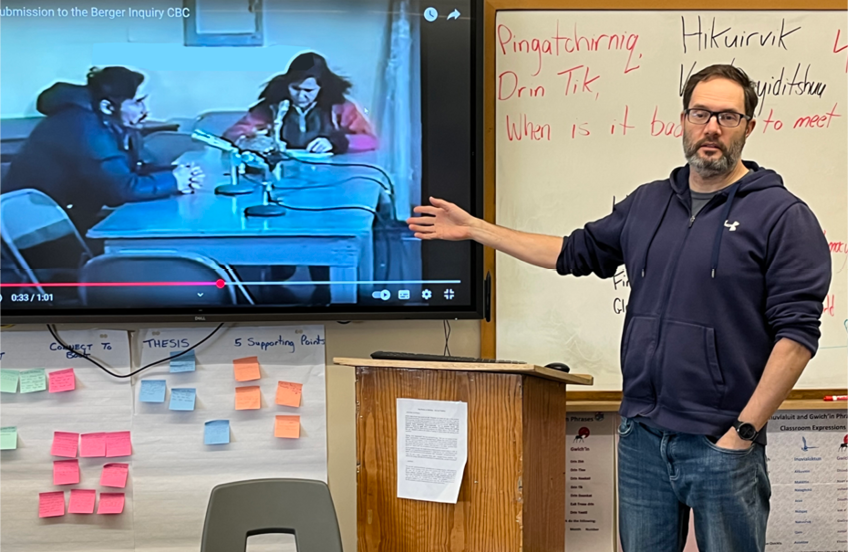

In my Opinion...

By Gene Jenks, East Three Secondary School, Inuvik

Students in Inuvik asked: Did the Canadian government make a wise decision when the

Cabinet allowed Dome Petroleum to drill in the deep waters of the Beaufort Sea?

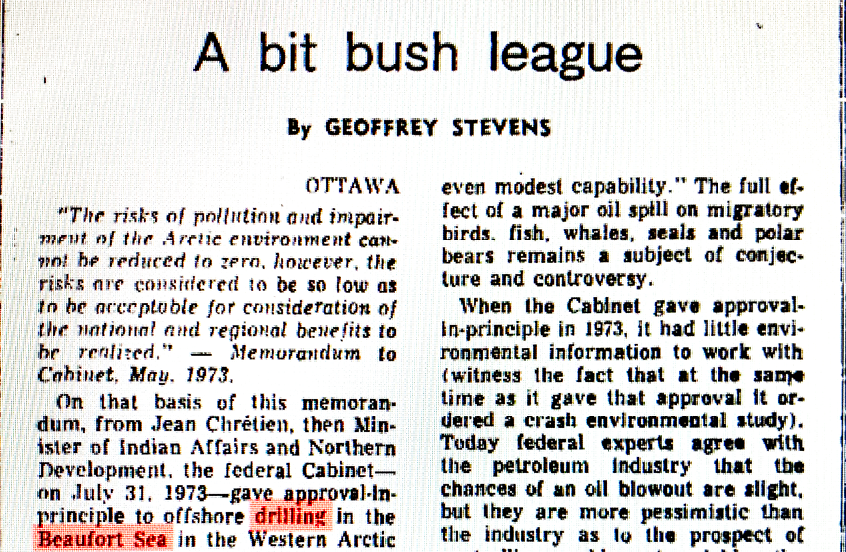

They read a editorial by Geoffrey Stevens. He led readers through a logical argument,

concluding that the decision to allow offshore drilling was “a bit bush league”.

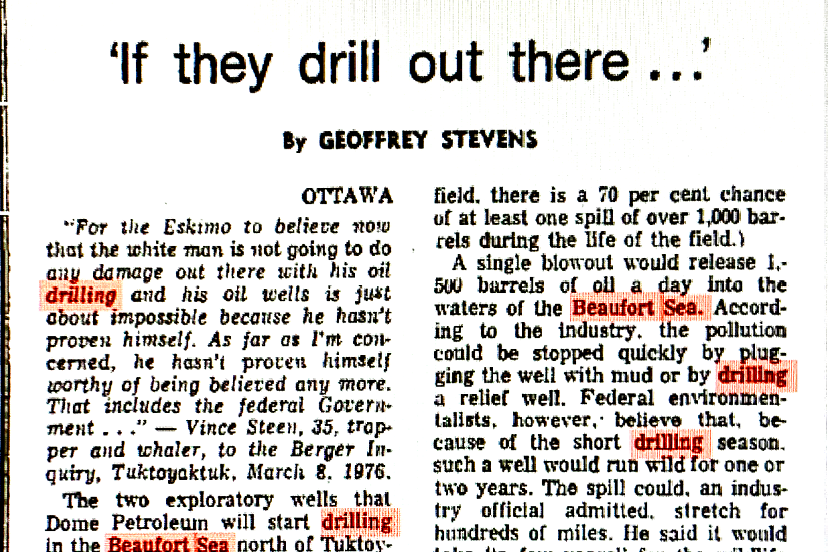

Then, students read a second editorial where Steven’s quoted Vince Steen’s speech from

Tuktoyaktuk. How was this argument different?

By then, the students were curious. Did the Dome drill ships encounter oil and gas? Did

the drilling end with a blowout? They dove into newspaper clippings to find out.

Gene Jenks asked each student to write an editorial to register an opinion on offshore

drilling in a clear and reasoned way. He offered three tips.

Tip#1

An editorial draws facts together to present

a logical argument in support of an opinion.

Editorial writers aim to persuade their

readers to consider the argument and adopt

a point of view.

Tip#2

Editorial writers begin by researching their

topic carefully. They make notes about the

facts that support different perspectives.

Then they carefully think through their

argument, developing a fair and balanced

pathway to their conclusion.

Tip#3

An editorial presents a challenge in the

opening paragraphs. The following paragraphs

may add facts to support this point of view,

or they may examine the weaknesses of

counter arguments. Or they may do both.

The goal is to lead the reader to agree with

the position taken in the editorial.

Students wrote editorials from two points of view, in favour and against offshore drilling.

Read Seanna’s editorial. Is she persuasive?

A Matter of Justice

By Seanna, East Three Secondary School, Inuvik

For over a thousand years, the lnuvial-

uit and other Indigenous people have

resided in the Arctic, with the sea and

land. They hunted, fished, and harvest-

ed throughout this large area, only har-

vesting what they required and mak-

ing sure nature’s cycles were preserved

for the next generation. But now the

balance is being threatened not by

anything they’ve done, but by power-

ful oil companies, about to drive into

the frigid core of the Arctic.

The attempt to drill the Beaufort

Sea is not an environmental issue; it’s

a matter of justice. It’s whether we lis-

ten to the voices of the people who’ve

cared for this land for hundreds of

years or silence them for the promise

of profit.

The risks have never not existed.

There are always the chances of pollu-

tion, of blowouts, of disastrous spills

that would take the Arctic ecosystem

decades or even centuries to recov-

er from. During the long winter, ice

covers the sea so that if a spill should

have occurred, the oil would effective-

ly wash up only under the ice, and far

beyond the reach of booms or clean-

up teams. Even in the summer, time is

short if there is a blowout, companies

would not have sufficient time to drill

a relief well before the ice returns, and

oil would move over the ocean all win-

ter.

And what has the industry said in

response? Less than promising prom-

ises and less-than-stellar plans. One

company mentioned its 4-foot booms

as a key part of its cleaning plan but

even the president of the drilling com-

pany, Gordon Harrison, admitted the

ice would bust them. If the president

himself is aware the technology won’t

work, how can we possibly trust that

the company is prepared?

Geoffrey Stevens spoke to the deep

suspicion Indigenous people have

when he said, “For the

Eskimo to believe now that the white

man is not going to do any more dam-

age out there with his oil drilling and

his oil wells is just about impossible

because he hasn’t proven himself.” His-

tory has repeatedly demonstrated that

commitments to safeguard the land

are just discarded when

fortunes are at stake.

Meanwhile, oil industry executives

like Jack Gallagher brush aside con-

cerns, saying, “Oil is

natural in the sea. Oil is formed when

animals in the sea die and decay. Peo-

ple get all upset about a little bit of oil

in the sea, but it is not a big issue.” That

approach ignores hard scientific reality

and ignores the human cost.

Oil spills are not little setbacks. They

kill marine animals, from whales and

seals to seabirds and fish. They destroy

the fragile food and wildlife that Arctic

communities depend on for survival.

Inuit don’t just rely on marine animals

for food, but also for their culture, their

society, and

themselves. An oil spill is not a small

environmental disaster, it1s an eco-

nomic and cultural

disaster that can move its way through

communities for generations.

Even after a spill has been “cleaned

up,” its effects still linger. Oil invades

sediments, poisons

fish and marine mammals, and dis-

rupts reproductive cycles. For societies

that live off such

species. It’s not just lost dollars it’ s

about lost traditions, lost understand-

ing, and lost ways of

living. It’s time we recognize what’s re-

ally on the line. Drilling in the Beaufort

Sea’s not a matter of energy policy or

corporate profit. It’s a matter of respect

for the rights of Indigenous peoples.

It’s a matter of protecting one of the

globe’s most fragile and essential eco-

systems. And it’s a matter of recogniz-

ing some dangers are just too great, no

matter how much oil might lie buried

under the ice.

Unless the companies behind Arc-

tic drilling can present a genuine fool-

proof, ice-tested clean-up plan and

unless they show they are prepared

to grant Indigenous people a genuine

voice, not just token consultation Arc-

tic drilling must not go ahead.

We owe it to the land. We owe it to

the wild. And most importantly, we

owe it to the people who have called

this place home for thousands of years.